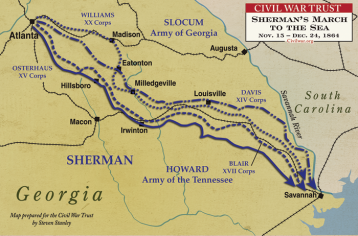

On this day in history, Union General William T. Sherman, leading some 60,000 soldiers, began a 285-mile march from Atlanta to Savannah, Georgia. As the American Battlefield Trust writes about Sherman’s motivations:

He sought to utilize destructive war to convince Confederate citizens in their deepest psyche both that they could not win the war and that their government could not protect them from Federal forces. He wanted to convey that southerners controlled their own fate through a duality of approach: as long as they remained in rebellion, they would suffer at his hands, once they surrendered, he would display remarkable largess.”

General William Tecumseh Sherman

After capturing Atlanta in early September, Sherman split his army, keeping 60,000 men and sending the rest back to Nashville with General George Thomas to deal with the remnants of General John Bell Hood’s Army of Tennessee, the force Sherman had defeated to take Atlanta.

Sherman wrote to his general in chief, Ulysses S. Grant, that if he could march through Georgia it would be “proof positive that the North can prevail.” He told Grant and Lincoln that he would not send couriers back, but to “trust the Richmond papers to keep you well advised.” Grant telegraphed back his blessings on November 2. Sherman loaded surplus supplies on trains and shipped them back to Nashville. On November 15, the army began to move, burning the industrial section of Atlanta before they left.

His forces followed a “scorched earth” policy, destroying military targets as well as industry, infrastructure, and civilian property, disrupting the Confederacy’s economy and transportation networks. The operation broke the back of the Confederacy and helped lead to its eventual surrender. Sherman’s decision to operate deep within enemy territory and without supply lines is considered to be one of the major campaigns of the war, and is considered by some historians to be an early example of modern total war.

On December 21, Savannah surrendered to Sherman. Sherman famously telegraphed President Lincoln, “I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the City of Savannah, with one hundred and fifty heavy guns and plenty of ammunition and about twenty-five thousand bales of cotton.”

On December 26, the president replied in a letter:

Many, many thanks for your Christmas gift, the capture of Savannah. When you were about leaving Atlanta for the Atlantic coast, I was anxious, if not fearful; but feeling that you were the better judge, and remembering that ‘nothing risked, nothing gained,’ I did not interfere. Now, the undertaking being a success, the honor is yours; for I believe none of us went further than to acquiesce.”

Filed under: legal | Tagged: Civil War, History | Leave a comment »