Jackie Robinson famously broke the color barrier in major league baseball when, in 1947, he signed on to play with the Brooklyn Dodgers. The first African American to play in the major leagues in the 20th century, Robinson was the target of “torrents of abuse,” as Robinson described it in his autobiography. Nevertheless, Robinson, as a National Archives post observes, “answered the people he called “haters” with the perfect eloquence of a base hit. In 1949, his best year, Robinson was named the league’s Most Valuable Player, and in 1962 he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. He retired from the major leagues in 1956.”

After Robinson retired from playing, he continued to advocate for Black civil rights. From the Archives:

Every American President who held office between 1956 and 1972 received letters from Jackie Robinson expressing varying levels of rebuke for not going far enough to advance the cause of civil rights.”

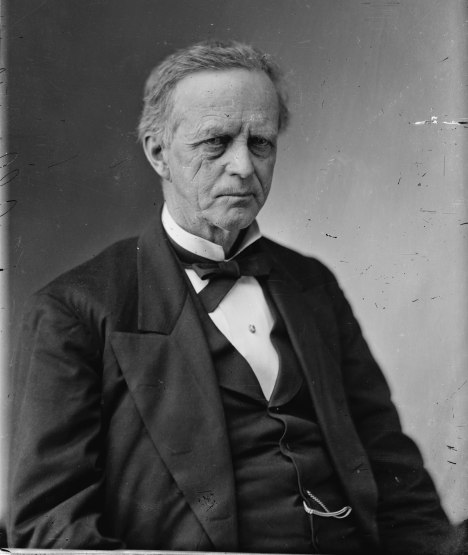

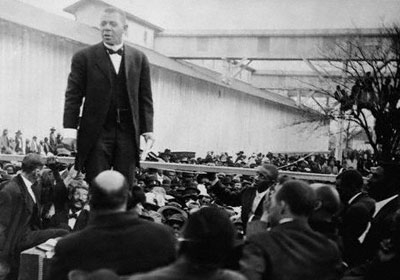

Jackie Robinson and President Dwight Eisenhower in the Oval Office, 1957.

Photograph Courtesy of the Dwight Eisenhower Presidential Library

On this day in history, Robinson sent a letter to President Dwight Eisenhower, following a speech by Eisenhower to Black leaders in which he implored Blacks to have “patience.” Robinson’s excellent rejoinder, with sentiments later echoed by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail” (written April 16, 1963) is worth quoting in full:

My dear Mr. President:

I was sitting in the audience at the Summit Meeting of Negro Leaders yesterday when you said we must have patience. On hearing you say this, I felt like standing up and saying, “Oh no! Not again.”

I respectfully remind you sir, that we have been the most patient of all people. When you said we must have self-respect, I wondered how we could have self-respect and remain patient considering the treatment accorded us through the years.

17 million Negroes cannot do as you suggest and wait for the hearts of men to change. We want to enjoy now the rights that we feel we are entitled to as Americans. This we cannot do unless we pursue aggressively goals which all other Americans achieved over 150 years ago.

As the chief of executive of our nation, I respectfully suggest that you unwittingly crush the spirit of freedom in Negroes by constantly urging forbearance and give hope to those prosegregation leaders like Governor Faubus who would take from us even those freedoms we now enjoy. Your own experience with Governor Faubus is proof enough that forbearance and not eventual integration is the goal the pro-segregation leaders seek.

In my view, an unequivocal statement backed up by action such as you demonstrated you could take last fall in dealing with Governor Faubus if it became necessary, would let it be known that America is determined to provide – in the near future – for Negroes – the freedoms we are entitled to under the constitution.

Respectfully yours,

Jackie Robinson

Filed under: legal | Tagged: Black History, Civil Rights | Leave a comment »