King Louis XVI of France was beheaded in January of 1793. Ten days later, France, already fighting Austria and Prussia, declared war on England, Holland, and Spain. Having helped America in her war of independence, France now felt entitled to reciprocation from the former colonies. To that end, France sent Edmond Charles Genêt, who called himself “Citizen Genêt” as minister to the United States, for the purpose of enlisting American assistance to the fullest extent possible.

Engraving of Edmond-Charles Genêt

Genêt’s mission, as recounted by Joel Richard Paul in Without Precedent: John Marshall and His Times, was to persuade the U.S. to help France liberate Canada, Louisiana, and Florida from rule by Britain and Spain. If the Americans refused to enter the war on France’s side, Genêt was instructed to “germinate the spirit of liberty” by instigating a popular uprising in favor of France. He had other assignments as well, all of which were designed to advance the position of France in the U.S. to the detriment of Britain.

Genêt launched an immediate campaign to realize his goals, taking assertive actions that amounted to “an astounding breach of diplomatic protocol and international law” (per Paul, p. 73).

President George Washington wanted the U.S. to remain neutral in the war between France and Britain, much to Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson’s chagrin. Jefferson, besotted with France as well as its revolution, fiercely opposed neutrality. Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, on the other hand, strongly supported it.

Jefferson had already been meeting secretly with Genêt, and was anxious for Genêt’s help to elect a republican majority in Congress in return for support for an alliance with France and a removal of tariffs on French imports. Paul writes:

Jefferson made clear that his enemies – the federalists [which included President George Washington], particularly Adams and Hamilton – were France’s enemies. . . . From these conversations, Genêt formed the misimpression that the president was irrelevant and that an appeal to Congress, or to the people directly, would be more effective.”

Genêt also confided his plans to arm regiments in South Carolina and Kentucky to attack Spanish holdings in Florida and Louisiana, and Jefferson helped put Genêt in touch with people who could help him.

Paul observes:

Jefferson’s relationship with the French envoy was ill-advised, probably illegal, and certainly disloyal to Washington.”

One of President Washington’s great fears was foreign entanglements, which he saw as inimical to the success of an American project in its infancy. Thus he resisted the attempt to draw the new United States into a European war, and on April 22, 1793, this day in history, he issued his Proclamation of Neutrality, declaring the U.S. a neutral nation in the conflict and threatening legal proceedings against any American providing assistance to the warring countries. Attorney General Edmund Randolph wrote the 293-word Proclamation for the president’s signature.

As a Mount Vernon history of the proclamation reports, it ignited a fire storm of criticism. Much of the American population, like Jefferson, sympathized with the cause of revolutionary France.

Republicans denounced the proclamation as exceeding the president’s constitutional powers. Using the pseudonym Pacificus, Alexander Hamilton wrote a series of essays in support of Washington’s authority to determine the country’s foreign relations. Jefferson, as was his usual modus operandi, remained silent in public while stealthily prodding his henchman James Madison to attack.

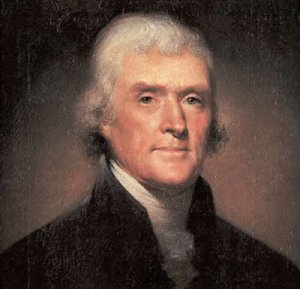

Thomas Jefferson

Jefferson sent a letter to Madison, bemoaning the fact that nobody was taking exception to the writings of Pacificus:

Nobody answers him, and his doctrine will therefore be taken for confessed. For god’s sake, my dear Sir, take up your pen, select the most striking heresies, and cut him to pieces in the face of the public. There is nobody else who can and will enter the lists with him.”

[When Jefferson himself was president, he of course would feel differently about presidential authority.]

The sniping over Genêt, Paul writes, would eventually lead to the spawning of two competing political parties. Madison (writing for Jefferson) and Hamilton (writing for Washington) provided each side of the growing partisan chasm between the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans with powerful talking points.

The tide of public opinion finally shifted when Hamilton leaked to the press information about Genet’s attempts to act against President Washington and destroy the new union.

Congress responded by passing the Neutrality Act in 1794, giving Washington’s policy the force of law. The act marked an acknowledgment by the legislative branch that foreign policy resided largely in the constitutional domain of the executive. It made it illegal for a United States citizen to wage war against any country at peace with the United States. [The act, repealed and replaced several times while also being amended, is in force as 18 U.S.C. § 960.]

On July 7, 1798, during the Quasi-War crisis in the presidency of John Adams, Congress formerly annulled the twenty-year-old Treaty of Alliance with France.

Filed under: legal | Tagged: George Washington, History |

Leave a comment