The New York Times reports that Americans spend $21 billion on chocolate every year, but the pandemic drove an even bigger boost in consumption.

Most anthropologists trace the use of cacao products to South America over 5,000 years ago.

The cacao tree (“cocoa” is a variant of “cacao”) is an equatorial plant with ovoid pods that grow directly from the trunk. The cacao beans are the seeds that grow inside the pod, which can take up to eight years to mature. After harvesting, the beans are fermented for up to a week to develop their flavors, and dried.

The dried beans are then roasted and cracked to separate the outer husks from the inner nibs.

Chocolate makers grind the nibs into what’s called chocolate liquor, and then grind them again after the addition of other ingredients such as sugar, milk power, and vanilla. Afterwards the chocolate is heated and cooled to specific temperatures so that it sets with the desired look and texture.

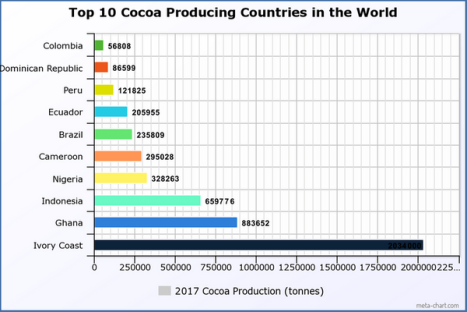

Today, South America is no longer the primary source for chocolate. Rather, multinational chocolate makers are heavily dependent on chocolate from West Africa. Fortune Magazine reports that more than 70% of the world’s cocoa is grown in the region, and the vast majority of that supply comes from two countries: Ivory Coast and Ghana, which together produce 60% of the global total.

So, you may ask, how did cacao production move from South America to West Africa?

INAFORESTA, in international voluntary group dedicated to the analysis and improvement of the relationships between cocoa, trees and forest worldwide, gives a capsule history on its website.

Spanish conquistador Hernán (or Hernando) Cortés, who went to Mexico, headed for the Aztec capital, and brought back chocolate to the Spanish court in 1528 along with the equipment necessary for brewing the drink. (In exchange, Cortés left the indigenous population with a number of Western diseases such as smallpox which caused huge fatalities, but we digress.)

The Spanish court went wild for the chocolate drink, adding cane sugar, vanilla, cinnamon and pepper.

As recounted in the book Bite-Sized History of France by Stéphane Hénaut & Jeni Mitchell, many Spanish Jews were involved in the chocolate trade and processing of chocolate, which meant that the industry moved around Europe as Jews were booted out of one country after another.

The grinding stone, or cocoa grinding stone, widely used in Spain until the 19th century, via Wikipedia

The industry first moved to France when Jews were banished from Spain and Portugal during the Spanish Edict of Expulsion in 1492 and the Portuguese Inquisition in 1536. Some of these Jews resettled in Bayonne in the Basque region of southwestern France and there built the country’s first chocolate factories.

Alas, the secrets of the craft became more widely known, along with a glimpse of the profits that could be made from it, and in 1761 the Jews were banned from the chocolate business by the city of Bayonne’s envious Christian leadership. Previously, in 1681, Jews had already been banned from making chocolate outside of the St. Esprit suburb in which they were forced to live. And while they could trade in the city proper, they could not sell chocolate on Sundays or Christian feast days. A Bordeaux court annulled the decree in 1767, because apparently many in Bayonne preferred the chocolate of the Jews. (See On the Chocolate Trail: A Delicious Adventure Connecting Jews, Religions, History, Travel, Rituals and Recipes to the Magic of Cacao by Deborah Prinz, 2013)

Hénaut & Mitchell recount that chocolate remained a luxury product until cacao was introduced to West African colonies, which helped reduce the price (because: slave labor). Cocoa plantations soon spread throughout the African continent. This led to the decline of production in South America, since it was cheaper not having to actually pay for labor, and easier to get the product back to Europe from Africa. Then the Industrial Revolution made possible the mass production of the chocolate bar, and eventually, as the authors write, “most people were eating rather than drinking chocolate.”

Today, while “slaves” aren’t used, laborers – not always working voluntarily – don’t exactly make a living wage.

As the Washington Post reports:

“According to recent research from Fairtrade International, the median income for a cocoa household in the Ivory Coast — the nation that produces more of the world’s cocoa than any other — is just $2,707 per year, an amount hovering close to the extreme poverty level of $2,276. The research of more than 3,000 households found that just 12 percent of those surveyed earned a living income.”

In Ghana, the second-largest cocoa producer – the average age of cocoa farmers is 52, and few young people see farming as an attractive vocation.

As Stéphane Hénaut & Jeni Mitchell explain in the book Bite-Sized History of France, “it is estimated that more than 2 million children labor on cacao farms, some trafficked from neighboring countries.”

A BBC article, for example, claimed that 15,000 children from Mali, some under age 11, were kidnapped and sold into slavery to work in cocoa production in Ivory Coast plantations:

In all, at least 15,000 children [from Mali] are thought to be over in the neighbouring Ivory Coast, producing cocoa which then goes towards making almost half of the world’s chocolate. Many are imprisoned on farms and beaten if they try to escape. Some are under 11 years old.”

A child rests with a machete at an Ivory Coast cocoa plantation. Children as young as 7 routinely work under dangerous conditions to harvest cocoa there, via U of Berkeley Law School

The Washington Post adds:

The scope and scale of the problems in cocoa are staggering: An estimated 2.1 million children are engaged in hazardous work in the fields of the Ivory Coast and Ghana alone. The average cocoa farming household in the Ivory Coast earns just 37 percent of a living income. The average age of farmers in Ghana — the second-largest cocoa producer — is 52, and few young people see farming as an attractive vocation.

Still, our research showed that cocoa continues to be the best among few options for millions of small farmers. In the Ivory Coast . . . there simply aren’t alternatives that provide farmers with comparatively stable incomes and a certain level of land security.”

Fortune Magazine journalists also investigated the issue, writing:

For a decade and a half, the big chocolate makers have promised to end child labor in their industry—and have spent tens of millions of dollars in the effort. But as of the latest estimate, 2.1 million West African children still do the dangerous and physically taxing work of harvesting cocoa. What will it take to fix the problem?

Apparently greed is an insuperable barrier. The Washington Post reports that the world’s largest chocolate companies promised to eradicate the epidemic of child labor nearly 20 years ago. But they missed deadlines to uproot child labor from their cocoa supply chains in 2005, 2008 and 2010.

In February, 2020, human rights advocates petitioned U.S. Customs and Border Protection to stop some of the world’s largest chocolate companies, including Nestlé; Mars; Hershey; Mondelez, the owner of the Cadbury brand; and other companies, from importing cocoa from Ivory Coast unless they could show that the chocolate was produced without forced or trafficked child labor.

A young boy from Burkina Faso, working in Ivory Coast cocoa fields, follows other children as they leave the cocoa farm where they work, via Washington Post

The U.S. State Department has indicated, however, that Ivory Coast appears ill-prepared to police child trafficking, saying the budget for the anti-trafficking program is “severely inadequate.” As State Department officials noted in a 2018 report, the primary police anti-trafficking unit is based in the nation’s economic capital, Abidjan, several hours away from the cocoa-growing areas, and its budget was about $5,000 a year.

Richard Scobey, President of the World Cocoa Foundation industry group, was opposed, out of concern, needless to say, for the poor people:

This irresponsible call for a U.S. ban on cocoa imports from Côte d’Ivoire will hurt, not help. It could push millions of poor farmers deeper into poverty, even though the vast majority of them are innocent of such practices, and threatens to damage the economy and security of a vital U.S. partner in West Africa.”

In the final analysis, chocolate companies do not want to give up their profits, and consumers do not want to give up their candy bars.

Major chocolate companies maintain, as they have claimed now for years, that they are working to improve social conditions and thus eliminate the factors that lead to child labor. But as of 2020, the New York Times reports, there are still no laws in America to require American companies not to use sources using child labor. Even if there were such laws, there remains the question of how effectively they could be enforced.

Dr. Maricel Presilla, a culinary historian in New Jersey, and author of The New Taste of Chocolate, Revised: A Cultural and Natural History of Cacao with Recipes,, observes:

“Everyone wants to be able to buy chocolate and go to heaven, but the issues are complicated.”

Leave a comment