Marie Tharp was born on this day in Michigan. During World War II, when so many men were unavailable for jobs usually denied to women, she was got accepted into the University of Michigan/Ann Arbor’s petroleum geology program, where she completed her master’s degree. She was then hired by Standard Oil in Oklahoma as a junior geologist.

However, because women weren’t permitted to go out into the field to look for oil and gas, she was stuck in an office, collecting maps and data from men doing the actual field work. She was bored, and took night classes at the University of Tulsa, earning her second bachelor’s degree in science.

In 1948, Tharp moved to New York City and eventually found drafting work with Maurice Ewing, the founder of the Lamont Geological Observatory (now the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory).

At Lamont, Tharp met Bruce Heezen, and in early work together they used photographic data to locate downed military aircraft from World War II. Eventually she worked for Heezen exclusively, plotting the ocean floor.

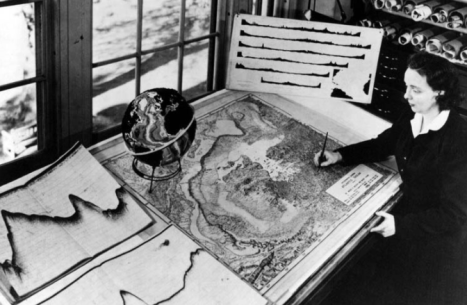

Marie Tharp at her drafting table in Lamont Hall circa 1961. (Credit: Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and the estate of Marie Tharp)

For the first 18 years of their collaboration, Heezen collected data on oceanic depths aboard the research ship Vema, while Tharp drew maps from that data, since women were barred from working on ships at the time. She was later able to join a 1968 data-collection expedition. She independently used data collected from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s research ship Atlantis, and seismographic data from undersea earthquakes. Her work with Heezen represented the first systematic attempt to map the entire ocean floor.

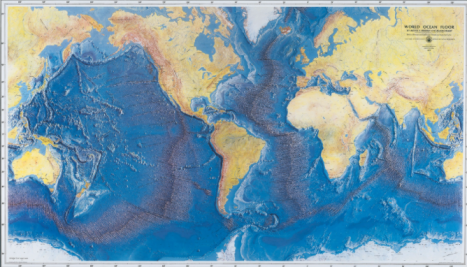

Before the early 1950s, scientists knew very little about the structure of the ocean floor. Piecing together maps that they made, she and Heezen revealed a 40,000-mile underwater ridge girdling the globe. With that discovery, they laid the foundation for later work that showed the sea floor spreads from central ridges and that the continents are in motion with respect to one another — a revolutionary and controversial theory among geologists at the time, but crucial to the development of plate tectonic theory.

Heezen was initially unconvinced as the idea would have supported continental drift, then a controversial theory. Instead, for a time, he dismissed her explanation as “girl talk”. (This was according to Tharp’s memoirs excerpted on the Woods Hole website, here.)

But as additional data confirmed her theory, Heezen at least shared their data at conferences. (Tharp recalled that after a talk by Heezen in a 1957 meeting, the eminent Princeton geologist Harry Hess, who later developed the theory of seafloor spreading, stood up and said, “Young man, you have shaken the foundations of geology!” She did not indicate whether or not Heezen credited her contributions.)

Tharp decided she could show everyone her theory was correct by publishing her maps. She and Heezen added data from other ocean mapping expeditions across the globe. Those data revealed similar ridge features in the Indian Ocean, Arabian Sea, Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, and the Pacific Ocean. Other data plotting earthquakes showed that wherever there was a mid-oceanic ridge, there were earthquakes.

he World Ocean Floor map was published in 1977 by the Office of Naval Research and is still in wide use today. (Credit: World Ocean Floor Panorama, Bruce C. Heezen and Marie Tharp, 1977. Copyright by Marie Tharp 1977/2003. Reproduced by permission of Marie Tharp Maps LLC and the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory)

In time, as Tharp wrote, “The borders of the plates took shape, leading rapidly to the more comprehensive theory of plate tectonics.” She added:

I worked in the background for most of my career as a scientist, but I have absolutely no resentments. I thought I was lucky to have a job that was so interesting. Establishing the rift valley and the mid-ocean ridge that went all the way around the world for 40,000 miles—that was something important. You could only do that once. You can’t find anything bigger than that, at least on this planet.”

Marie Tharp, July 2001. (Credit: Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and the estate of Marie Tharp)

Eventually, Marie Tharp received recognition for her accomplishments. She was given awards in geography in 1978, 1996, 1999, and 2001. In 1997, Tharp received double honors from the Library of Congress, which named her one of the four greatest cartographers of the 20th century and included her work in an exhibit in the 100th-anniversary celebration of its Geography and Map Division.

Tharp died of cancer in Nyack, New York, on August 23, 2006, at the age of 86.

Leave a comment