American history tends to emphasize the lives of a select group of Founding Fathers and largely ignore others. Benjamin Rush falls into the latter category, but as Unger documents, this neglect is unjustified.

Benjamin Rush was born on December 24, 1745, near Philadelphia. He completed medical training at the University of Edinburgh, and practiced for a while in London, where he became friends with Benjamin Franklin. When he returned to Philadelphia to work, his ties to Franklin helped him establish relationships with many leading thinkers in the American colonies.

Rush encouraged Thomas Paine to write the pamphlet, “Common Sense,” suggested the title to Paine, contributed ideas for its contents, and helped distribute it. Rush was one of the 56 signers of the Declaration of Independence, an act of treason at that time that could have gotten him executed.

In 1776 at age 31, Rush married 16-year-old Julia Stockton, with whom he eventually fathered 13 children, although four died shortly after birth. (One of his sons, Richard, born in 1780, later served in the cabinets of James Madison, James Monroe, John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, James K. Polk, and Zachary Taylor.) Since Rush was away a lot on either medical or political duties, much of what we know of his life comes from his voluminous correspondence with Julia.

During the Revolutionary War, Rush clashed with just about everyone in power over the need for better medical supplies and treatment of injured soldiers, but since George Washington couldn’t even get clothes or food for the troops, “luxuries” such as medical care inevitably fell by the wayside.

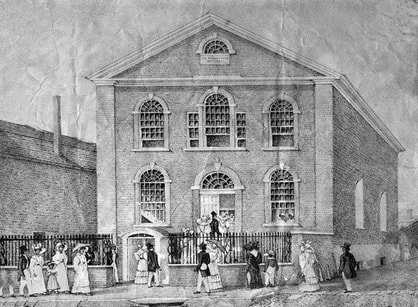

Rush was a devout Presbyterian, and his religious faith led him to join the abolitionist movement in Philadelphia, and to help raise money for the African Episcopal Church of Philadelphia.

Unger apprises us that Rush made a great deal of innovations in medicine in the early years of America, including a campaign to treat mental conditions as illnesses rather than crimes (Rush was later dubbed the “father of American psychiatry” by the American Psychiatric Association); a push for geriatric medicine; and encouragement of veterinary medicine, inter alia. He fought for better conditions in prisons, more sanitation in city streets, education for women, and free medical care for the poor. He was appointed to a professorship to the Philadelphia Medical School (which later merged with the University of Pennsylvania Medical School), and wrote the first American chemistry textbook (one of over 85 publications, not including letters and essays).

Rush met John Adams in 1774 and they became close friends, despite the fact that Rush was also close to Jefferson – Adams’s ideological opposite, whom Rush met in 1775. Late in life, Rush convinced Jefferson and Adams to reconcile and to begin to correspond with one another again.

Unger spends a great deal of time in the book on Rush’s devotion to the practice of bloodletting for the treatment of just about anything, but especially yellow fever, which was particularly a problem in the hot Philadelphia summers. Rush drew an association between pools of stagnant water and the disease, but had no idea it was the mosquitoes drawn to the water that caused the malady; rather, he thought it was due to inhaling the bad air from the stagnant water. Nevertheless, by his advocacy for better city sanitation, he inadvertently helped eliminate some mosquito breeding grounds. But his obsessive push for bleeding as well as purging of the bowels through calomel (a mercury compound) garnered him vociferous opponents. This “depletion therapy” was based on his belief that all diseases were caused by friction between the blood and blockage of bile in the intestines. Rush was dogmatic, determined, and convinced he had been chosen by God to save people.

An article for the Lancaster Pennsylvania Medical Heritage Museum by Eli Schneck notes:

“His excessive bloodletting and heroic purges with calomel were so extreme that his patients died before they showed signs of mercury poisoning, leading him to believe that people were dying of the disease instead of prescription cure.”

One persistent critic, William Cobbett, published relentless attacks on Rush and his treatment in his newspaper, “Porcupine’s Gazette.” In 1799, Rush brought a successful libel suit against Cobbett.

He thereby survived (however unjustifiably) the attacks on his credibility and continued to teach depletion theory as standard medical practice. Schneck writes:

“As a gifted lecturer and prolific writer, his theory of medicine spread across the United States and Western Europe. He influenced over 3,000 students at the College of Philadelphia Medical School over the course of his 40 years of teaching. His students and writings are responsible for the infamous heroic age of medicine where patients were bled and purged with a ferocity and horror never seen before in medicine.”

Thus, in 1799, when former President George Washington became ill with an acute respiratory illness, his death was hastened by the removal of over eighty ounces of blood (some 40% of the total blood composition) from his body.

Rush died on April 19, 1813, of “typhus,” which in those days was a rather generic term and could have been pneumonia.

Evaluation: Rush’s legacy is interesting and complex. Unger obviously admires Rush a great deal. But as Baylor Medical Professor Robert North opined:

“Benjamin Rush has been hailed as ‘the American Sydenham’ [Thomas Sydenham was an influential English physician in the 1600s], ‘the Pennsylvania Hippocrates,’ the ‘father of modern psychiatry,’ and the founder of American medicine. The American Medical Association erected a statue of him in Washington, DC, the only physician so honored. A medical school is named after him. He was a prolific and facile writer and a very influential teacher. Yet, the only enduring mark he has left on the history of American medicine is his embarrassing, obdurate, messianic insistence, in the face of all factual evidence to the contrary, on the curative powers of heroic depletion therapy. Rush’s thinking was rooted in an unscientific revelation as to the unitary nature of disease, which he never questioned. He viewed nature as a treacherous adversary to be fought on the battleground of his patients’ bodies.”

It is presumably because of his controversial medical career that his many contributions to the early political development of the country have been overlooked. Thanks to Unger, a prolific historian of the founding fathers, this omission may be remedied.

Rating: 4/5

Published by Da Capo Press, an imprint of Hachette Books, 2018

Leave a comment