So many books have been called “magisterial” that the impact of the word has been diluted. Thus I fear it will not suffice to convey what a monumental work MacCulloch has produced. Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years covers the story of Christianity with (pretty much) all the variations, heresies, and twists and turns from its origins in Judaism, to the history of the early Christian Church, through the Protestant Reformation and Catholic Counterreformation, and up to the present day. And it does so with sympathy and wit. I must warn the casual reader that it is over one thousand pages long, so be prepared to spend a lot of time with Professor MacCulloch.

The revelations contained in MacCulloch’s account are too numerous and complex to summarize. Instead, I will just note a few of the author’s more interesting observations.

If Jesus ever wrote anything, it did not survive in the historical record. Moreover, there appear to be no contemporaneous written mentions of Jesus. The gospels, both canonical and apocryphal, as the well as two references to him by secular historians, were written at least a generation after his death. The four canonical gospels themselves appear to have been written by early followers who had agendas that differed from one another’s. Much of MacCulloch’s history describes the efforts of various individuals or groups to control the story and the meaning of Christ’s life that would be included in the official canon. (The earliest surviving complete list of books that we would recognize as the New Testament comes as late as 367 C.E.)

The author notes the contradictions in the alternate stories of the birth of Jesus found in Mathew and Luke [Mark and John are silent on that issue]. He summarizes, “We must conclude that beside the likelihood that Christmas did not happen at Christmas, it did not happen in Bethlehem.”

Early Christians (most of whom were converted Jews) did not want to be enemies of the Roman Empire, so they played down the role of Roman authorities in the execution of Jesus, preferring to shift the blame to Jews who did not convert.

As for the Resurrection, the central event of Christianity, MacCulloch calls it “not a matter which historians can authenticate; it is a different sort of truth, or statement about truth. It is the most troubling, difficult affirmation in Christianity….”

The problem of biblical interpretation is a theme that runs through the entire history of Christianity. Origen, an early Christian theologian, asks, “who is so silly as to believe that God, after the manner of a farmer, planted a paradise eastward in Eden, and set in it a visible and palpable tree of life, of such a sort that anyone who tasted its fruit with his bodily teeth would gain life?” MacCulloch writes, “Origen might be saddened to find that seventeen hundred years later, millions of Christians are that silly.”

MacCulloch treats Roman Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, and Protestantism equally and dispassionately. He seldom loses sight of his role as historian rather than apologist or debunker. Occasionally, however, his sense of irony cannot be contained, as when he describes the appearances of the Blessed Virgin at Lourdes shortly after Pope Pius IX had used his infallible authority to define and promulgate the doctrine that Mary had been conceived without original sin. Noting that the many appearances of Mary in the nineteenth century were surrounded by fierce controversies, he observed:

Our Lady showed her approval of the Pope’s action by appearing at Lourdes in the French Pyrenees only four years after the Definition, announcing . . . with a fine disregard for logical categories, ‘I am the Immaculate Conception….’”

Over the next few months, it was said that those who questioned Our Lady “found themselves troubled by poltergeist-like phenomena and specifically directed storms….[or] acute diarrhoea. These aspects…zestfully narrated by locals at the time, have subsequently been edited out of the shrine’s official narratives; Our Lady has become a much better behaved Virgin.”

Artistic rendition of the first appearance of the Blessed Virgin Mary in 1858 to 14-year-old Marie Bernade at Lourdes

The role of the mother of Jesus has been a source of contention between the various strands of Christianity. Without explicitly taking sides, the Protestant MacCulloch notes that a proclamation of Mary’s perpetual virginity has caused devout Catholic commentators to appear clumsy in handling “clear references in the biblical text to Jesus’s brothers and sisters, who were certainly not conceived by the Holy Spirit.”

MacCulloch writes cogently and non-judgmentally about the millennium-long struggle for pre-eminence between pope and emperor for control of the Church.

MacCulloch’s devotes only two pages to the role of religion in the founding of the American Republic, but those pages should be required reading for candidates for national office. He notes that at the time of the American Revolution, only around 10% of the American population were formal Church members. Many of America’s founding fathers were deists, creatures of the Enlightenment rather than practicing Christians. Thomas Jefferson “deeply distrusted organized religion and spoke of the Trinity as ‘abracadabra…hocus-pocus…a deliria of crazy imaginations, as foreign to Christianity as is that of Mahomet.’” Washington never received Holy Communion, and was inclined in discourse to refer to providence or destiny rather than to God.

MacCulloch summarized the influence of religion among the founding fathers as follows:

What this revolutionary elite achieved amid a sea of competing Christianities, many of which were highly uncongenial to them, was to make religion a private affair in the eyes of the new American federal government. The constitution which they created made no mention of God or Christianity (apart from the date by ‘the Year of our Lord’). That was without precedent in Christian polities of that time, and with equal disregard for tradition…the Great seal of the United States of America bore no Christian symbol but rather the Eye of Providence, which if it recalled anything recalled Freemasonry….The motto ‘In God We Trust’ only first appeared on an American coin amid civil war in 1864, a very different era, and it was 1957 before it featured on any paper currency….Famously, Thomas Jefferson wrote as president…that the First Amendment…had created a ‘wall of separation between Church and State.’”

Evaluation: This book is truly comprehensive in scope. Any review simply cannot touch upon all the issues covered in the book without being absurdly long. MacCulloch is meticulous in referring to, analyzing, and putting into historical perspective just about every known variety of Christianity: Baptists, Methodists, Lutherans, Mormons, several varieties of Orthodox practice, Coptics, Arians, Pentecostals, and a host of lesser known offshoots and heresies. All get their due. Even if you don’t (yet) know the difference between a Miaphysite and a Chalcedonian Christian, this book contains a great deal to learn and ponder.

Rating: 5/5

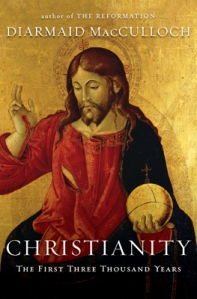

Note: Maps and pictures are included with the text.

Published by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA), Inc., 2010

Leave a comment