This is yet another book that, while focused primarily on John Marshall, compares the legacies Marshall with his political rival, Thomas Jefferson. Both men made essential contributions to the early republic. And like every other historian I have read, in this author’s assessment, Marshall was the better man.

Joel Richard Paul studied at Amherst College, the London School of Economics, Harvard Law School, and the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. He teaches international economic law, foreign relations, and constitutional law at the University of California Hastings Law School, serving as the Associate Dean at the time of publication. He provides an astute analysis of John Marshall’s greatest cases, and does not hesitate to point out instances when Marshall “was no purer than his contemporaries.” Yet he clearly finds much to admire about John Marshall.

As he notes in his introduction:

None of the founding generation of American leaders had a greater impact on the American Constitution than John Marshall, and no one did more than Marshall to preserve the delicate unity of the fledgling republic.”

This was done by a man whose only formal education was one year of grammar school and six weeks of law school! Yet this self-taught man went on to exhibit not only a wide-ranging erudition but a sense of honesty and decency that won over even those who began as his opponents. (The exception of course was the intractable Jefferson, who saw Marshall as standing in the path of Jefferson’s control of all branches of government.) Marshall’s special forte was the art of compromise, which he employed both as a diplomat in France, and on the court which he led for thirty-four years, longer than any other chief justice. More critically, he single-handedly established the court’s importance and supremacy in American life.

Marshall was born on September 24, 1755 in Germantown, Virginia, the eldest of fifteen children. His mother was a first cousin of Thomas Jefferson’s mother but the families were not close. Because of a scandal involving Marshall’s maternal grandmother, the Marshall side of the family was disinherited, and Jefferson’s family got most of the wealth. As Paul observes:

As a result, Thomas Jefferson grew up at Tuckahoe with five hundred slaves. There he enjoyed enormous privilege and wealth. His cousin John Marshall and his fourteen siblings grew up on the frontier working the stony soil on their father’s modest farm.”

Paul avers that Marshall grew up without resentment; rather, he moved fluidly between classes and had the confidence to believe he could elevate his station. Unlike Jefferson, who grew up with education, advantages, and was groomed for leadership, Marshall had to rely on determination and self-invention. His upbringing also provided him with more compassion than Jefferson, and a more generous and humane nature. Paul opined:

Though Marshall belonged to the party of elites, he practiced republicanism in his everyday life. By contrast, Jefferson preached democracy but lived more like the European aristocrats he despised.(p. 235)”

Jefferson, in Marshall’s view, as Paul contends, “lacked genuine empathy and embodied precisely the kind of elitism that he attacked in theory. He could never be trusted to act in the interests of the nation.”

When President John Adams nominated Marshall to be Chief Justice right before he ceded the presidency to Thomas Jefferson, “the Supreme Court was regarded as nothing more than a constitutional afterthought.”

Jefferson and the Republican Congress wanted to emasculate the judiciary, and took numerous steps (only some of which were successful) to do so. But by the time Marshall’s tenure ended in 1835, he had “elevated the dignity of the Supreme Court as the final arbiter of the Constitution’s meaning.”

Importantly, Marshall was able to win over the other justices on the court, even those appointed by Jefferson specifically to oppose Marshall. Paul posits that Marshall’s collegiality as well as “sheer personality and intellect” won over “even the most resolute colleague.”

How he did this – and sometimes he acted less than exemplary in his efforts to outwit the attacks on judicial independence and rule of law by Thomas Jefferson and later Andrew Jackson – is the subject of Paul’s book. Paul tells the story mostly through an explication of the cases that came before the court, because the fact was that many of them represented competing visions of power between Jefferson and Marshall.

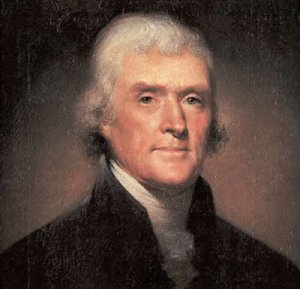

Thomas Jefferson

I was especially surprised to learn about Marshall’s sneaky manipulation in seminal cases like Marbury vs. Madison, but I believe, as Marshall seems to have done, that the end justified the means. In any event, Marshall was no less sneaky and manipulative than Jefferson, but Marshall, in my view, was more often on “the side of the angels.”

Paul informs us that prior to Marshall’s tenure, each justice issued his own individual opinion seriatim. Marshall thought that the Court’s authority would be more persuasive and the law more clarified if he could forge a single decision on behalf of the entire Court. Thus, during his thirty-four years as chief justice, Marshall personally wrote 547 opinions. Of these, 511 were unanimous.

It is important to note the irony that Marshall, a “founding father,” rejected a strict construction of the Constitution and insisted on interpreting it as a living document that responded to the needs and demands of a growing nation.

Marshall made a number of courageous decisions that inspired a great deal of enmity in his detractors, such as clearing Aaron Burr of treason charges in 1807. This charges were pushed forward by President Jefferson for the principal reason that Burr was a powerful political enemy. But the penalty for treason was death, and there was a total lack of evidence against Burr.

Portrait of Burr, undated (early 1800s)

While Paul is generally willing to expose Marshall’s warts, he gives him a pass when it comes to slavery. Paul writes:

Marshall was not free of racial prejudice, and he did enjoy the comforts that his household slaves provided to him. Marshall’s attitude toward African Americans was paternalistic. He viewed his slaves as family members who needed his guidance and support. . . . It appears that Marshall treated his slaves humanely, and on at least one occasion, he paid for a doctor to care for a slave woman who was ill.”

In his conclusion he repeats the assertion that Marshall had a “generous and humane relationship with his slaves” (p. 437).

[This seems to me to be a quite specious argument. Can you be “humane” toward someone you hold in ownership, house in your basement, trade like baseball cards at a cattle market, and buy and sell at your whim? Okay so maybe you don’t use a whip and don’t use rape – should that be touted as laudatory? I would accept “less horrible” perhaps, but not “humane.”]

Paul Finkelman, writing in Supreme Injustice: Slavery in the Nation’s Highest Court (Harvard, 2018) contends that biographers are reluctant to tarnish the picture of “our greatest chief justice.” But Marshall’s relationship with slavery was an important influence on his jurisprudence and therefore deserves closer scrutiny.

Marshall accumulated more than 150 slaves in his lifetime, while also giving around seventy slaves to two of his sons. When he died, Marshall did not arrange to free any of his slaves, unlike some other prominent Virginians in his time, including George Washington. No evidence remains as to how he actually treated his slaves.

But we can learn something from his jurisprudence, Finkelman argues. It was “hostile to free blacks and surprisingly lenient to people who violated the federal laws banning the African slave trade.” (Finkelman at 34) For Marshall serving on the court, Finkelman argues, “slaves were another form of property subject to litigation….”

Finkelman cites John Marshall in his “Memorial: To the General Assembly of Virginia,” December 13, 1831, available in Papers of Marshall, 12:127 contending that free blacks in Virginia were worthless, ignorant, and lazy, and that they were “pests” that should be removed from the state.” (Finkelman at 51)

It is truly tragic that Marshall felt this way, for he might have made a difference. As Marshall said in his opinion exonerating Burr, and acknowledging the unpopularity of the ruling:

That this court dares not usurp power is most true. That this court dares not shrink from its duty is not less true. No man is desirous of placing himself in a disagreeable situation. No man is desirous of becoming the peculiar subject of calumny. . . . But if he have no choice in the case, if there be no alternative presented to him but a dereliction of duty or the opprobrium of those who are denominated the world, he merits the contempt as well as the indignation of his country who can hesitate which to embrace. That gentlemen, in a case the most interesting, in the zeal with which they advocate particular opinions, and under the conviction in some measure produced by that zeal, should, on each side, press their arguments too far, should be impatient at any deliberation in the court, and should suspect or fear the operation of motives to which alone they can ascribe that deliberation, is, perhaps, a frailty incident to human nature; but if any conduct on the part of the court could warrant a sentiment that it would deviate to the one side or the other from the line prescribed by duty and by law, that conduct would be viewed by the judges themselves with an eye of extreme severity, and would long be recollected with deep and serious regret.”

Evaluation: I love reading histories of John Marshall – how can anyone with an interest in the law and in this country not find fascinating the court cases that shaped all subsequent jurisprudence as well as the relationship among the three branches of government? The fact that relationship is now imperiled is all the more reason to study how and why these struggles were worked out in the past, and to what effect.

Rating: 4/5

Published by Riverhead Books, 2018

Filed under: legal | Tagged: Book Review, History, Jefferson, SCOTUS |

Leave a comment