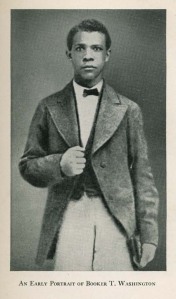

Booker T. Washington was born on April 5, 1856 near Hale’s Ford, Virginia on a tobacco plantation. He was born into slavery to Jane, an enslaved Black woman impregnated by a white man. He, his siblings, and mother gained freedom after the Civil War and the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment.

Washington’s mother was a major influence on his schooling. Even though she couldn’t read herself, she bought her son spelling books so he could learn to read. She then enrolled him in an elementary school, where Booker took the last name of Washington because he found out that other children had more than one name. He worked with his mother and other free Blacks as a salt-packer and in a coal mine. He was hired as a houseboy for Viola Ruffner, whose husband owned the salt-furnace and coal mine. Booker’s diligence impressed Mrs. Ruffner, and she encouraged him to attend school. Soon he sought more education than was available in his community.

In 1872 at the age of sixteen, Washington enrolled at the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, in Hampton, Virginia. Students with little income such as Washington could work at the school to pay their way. The normal school (teachers college) at Hampton was founded to train teachers and was chiefly funded by church groups and religious individuals. From 1878 to 1879 he attended Wayland Seminary in Washington, D.C., and returned to teach at Hampton. Soon, Hampton president Samuel C. Armstrong recommended Washington to become the first principal at Tuskegee Institute, a similar school being founded in Alabama. Such positions heading schools, even Black schools, had traditionally been held by whites. Booker T. Washington was 25 years old.

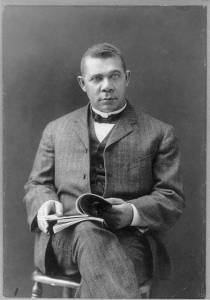

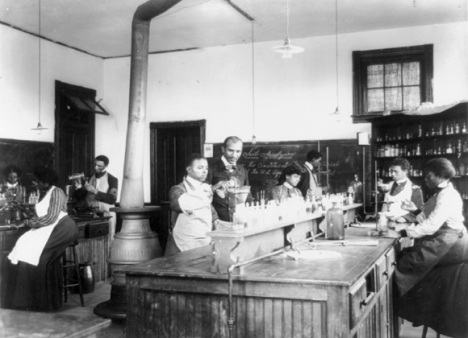

The new school opened on July 4, 1881, initially using space rented from a local church. The next year, Washington purchased a former plantation, which became the permanent site of the campus. Under his direction, his students literally built their own school: constructing classrooms, barns and outbuildings; growing their own crops and raising livestock, and providing for most of their own basic necessities. Both men and women had to learn trades as well as academics. The Tuskegee faculty utilized each of these activities to teach the students basic skills to take back to the mostly rural Black communities throughout the South. The school later grew to become the present-day Tuskegee University.

Tuskegee provided an academic education and instruction for teachers, but placed emphasis on providing Black males with practical skills, such as carpentry and masonry, which many would need for the rural lives most Blacks led in the South. The Institute illustrated Washington’s philosophy about his race. His theory was that by providing needed skills to society, African Americans would gain acceptance by white Americans. He believed that Blacks would eventually gain full participation in society by showing themselves to be responsible, reliable American citizens. Washington was head of the school until his death in 1915.

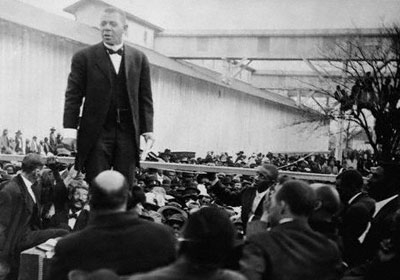

Washington gained national prominence in 1895, after a famous speech in Atlanta where he called for racial conciliation and urged Blacks to focus on economic self-advancement. The address would make him the central figure in American race relations for the next two decades.

His 1901 autobiography, Up From Slavery, was translated into seven languages. Washington, as the guest of President Theodore Roosevelt in 1901, was the first African-American ever invited to the White House. (This event caused such an uproar, however, that Roosevelt never repeated it.) Andrew Carnegie called him the second father of the country. Many of America’s other moneyed men, including John D. Rockefeller and J.P. Morgan, were admirers and major benefactors to the Tuskegee Institute. Harvard and Dartmouth gave him honorary degrees (in 1896 and 1901, respectively). Mark Twain and William Dean Howells sang his praises, the latter calling him “a public man second to no other American in importance.”

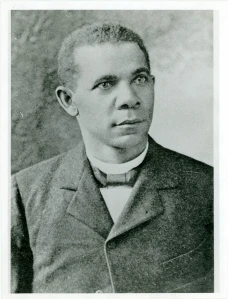

Late in his career, Washington was criticized by leaders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which was formed in 1909. W.E.B. Du Bois especially favored a harder line on activism to achieve civil rights. He labeled Washington “the Great Accommodator,” arguing that political power was necessary to protect any economic gains. Washington’s response was that confrontation could lead to disaster for the outnumbered Blacks. He believed that cooperation with supportive whites was the only way in the long run to overcome pervasive racism. Nevertheless, Washington quietly contributed money for court challenges to the segregation and disfranchisement of Blacks. In his public role, he believed he could achieve more by skillful accommodation to the social realities of the age of segregation. Through his own personal experience, Washington knew that good education was a powerful tool for individuals to collectively accomplish that better future.

Washington’s reputation among Blacks grew tarnished again in the radical 1960’s. Appeasement was rejected in favor of confrontation. Even Martin Luther King, Jr.’s style was bitterly contested by more radical Black activists.

Washington was not as accommodating as he seems to modern eyes. During his lifetime, Washington was fighting an upsurge in white backlash against Reconstruction as well as a revival of the Ku Klux Klan. Whites, particularly in the South, were opposed to giving Blacks educational opportunites, preferring that they had no options but to sign “contracts” that put them in virtual bondage to white employers. Booker T. Washington fought aggressively just to give Blacks the chance to learn. Furthermore, his efforts at fund-raising spurred philanthropic contributions to the construction of more schools throughout the South.

Washington did make some public protests against discrimination, writing in 1899, “I do not favour the Negro giving up anything which is fundamental and which has been guaranteed to him by the Constitution of the United States.”

On November 14, 1915, Washington died at the age of 59 from hypertension and arteriosclerosis. He was buried on the campus of Tuskegee University near the University Chapel. At his death Tuskegee’s endowment exceeded $1.5 million in 1915 dollars. His greatest life’s work, the work of education of Blacks in the South, was well underway and expanding.

You can read Up From Slavery online here.

Filed under: History | Tagged: Black History, History |

Leave a comment