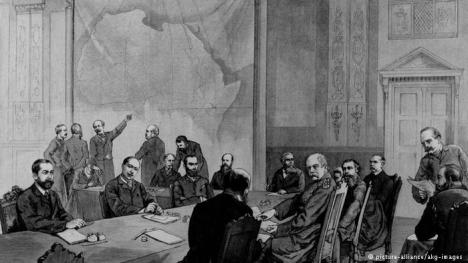

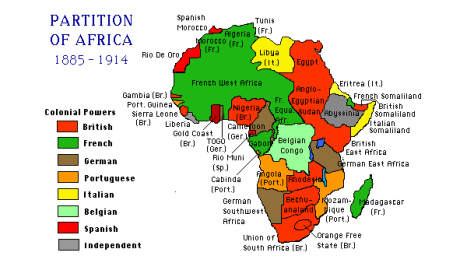

On this day in history, an act was passed “In the Name of God Almighty” by plenipotentiaries of Great Britain, Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, Portugal, Russia, Spain, Sweden and Norway, Turkey and the United States respecting the following:

(1) Freedom of Trade in the Basin of the Congo;

(2) The Slave Trade;

(3) Neutrality of the Territories in the Basin of the Congo;

(4) Navigation of the Congo;

(5) Navigation of the Niger; and

(6) Rules for the Future Occupation on the Coast of the African Continent.

Note that although this Conference was held to negotiate rights in Africa, no representatives of Africa were present.

The map on the wall in the Reich Chancellery for the Conference of Berlin was five meters (16.4 feet) tall.

The signatories were after wealth, cheap labor, and lebensraum. While some of the elements of the Conference sound liberal – for example, the agreement to interdict and suppress the slave trade – as human rights writer Edwin Black points out, part of the motive was to keep able-bodied Africans in Africa in order to serve as slaves for the colonizing powers.

Black also reports on the conditions in the four territories colonized by Germany (Togoland, the Cameroons, Tanganyika, and today’s Namibia). He writes:

Once entrenched, the German minority established a culture of pure labor enslavement. Tribeswomen were subjected to incessant and often capricious rape—and not infrequently, their men were killed while attempting to defend them. Whites routinely stole the possessions of natives, such as cattle, and found ways to seize ancestral lands over trivialities. Confiscation was often facilitated by predatory European lending practices enforced at gunpoint by the German military.”

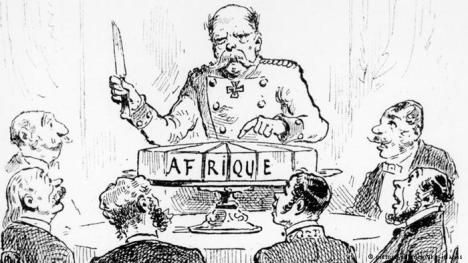

Unfortunately, Germany wasn’t the only bad actor in this play. The Congo “Free State” was established at this Conference, by which this area was confirmed as the private property of the Congo Society. This allegedly philanthropic society was founded in 1876 by King Leopold II of Belgium.

Belgium’s King Leopold II dividing up the spoils of Africa and claiming the Congo as his own private state.

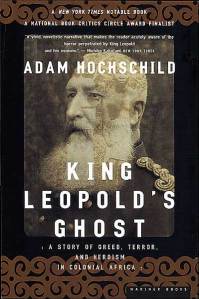

Adam Hochschild, an award-winning author of history, describes in gory detail in the book King Leopold’s Ghost the mass murder in the Congo that took place under the aegis of Belgium’s King Leopold II, mostly between 1890 and 1910. Greed for ivory, land, and rubber was behind the drive by Leopold that is thought to have reduced the population of the Congo by half: an estimated five to ten million lives lost. This figure does not include the numerous people subjected “merely” to amputation of hands and/or feet, an apparently common punishment meted out to family members of recalcitrant workers. (Cutting off hands was also the practice subsequent to executions to prove one had not “wasted” ammunition on nonhuman targets. Children were often killed with the butt of guns, also to save ammunition.)

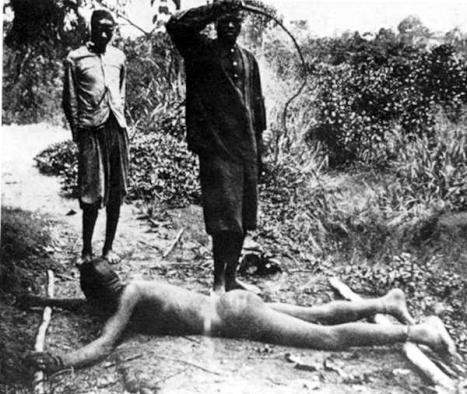

Inhabitants were used as porters – taking luggage, wine, and pâté inland for the white overseers, and bringing back ivory and rubber. They also had to harvest the ivory and rubber and process it prior to transportation. Porters were generally chained together by the neck, so that, for example, if one fell into the Congo while working on a bridge, the whole line would be dragged in as well, meaning certain death for all of them. Women were imprisoned and chained (and often raped) while the men were out gathering rubber, to ensure their return. Food allotments for workers were not generous, and punishment was meted out with the chicotte, a whip made out of dried hippopotamus hide cut into a sharp-edge strip. Beatings could be fatal. It was also not unusual for whole villages to be burned and their inhabitants executed as ‘examples” to other villages.

The author maintains that Europeans of Leopold’s time thought of Africa “as if it were just a piece of uninhabited real estate to be disposed of by its owner.” But more than that, the black inhabitants were regarded as less than human beings. Hochschild pauses in his tale of horror to ask:

What made it possible for the functionaries in the Congo to so blithely watch the chicotte in action and … deal out pain and death in other ways as well? To begin with, of course, was race. To Europeans, Africans were inferior beings: lazy, uncivilized, little better than animals. … Then, of course, the terror in the Congo was sanctioned by the [white] authorities. For a white man to rebel meant challenging the system that provided your livelihood [as well as a very good livelihood for your superiors. Leopold himself is estimated to have taken some $1.1 billion (in today’s dollars) in profits]. Finally when terror is the unquestioned order of the day, wielding it efficiently is regarded as a manly virtue, the way soldiers value calmness in battle.”

While most of his book focuses on the Congo, Hochschild’s last chapter summarizes the situation in some of the other colonial possessions. The French Congo, for instance, has a similar legacy:

In France’s equatorial African territories…the amount of rubber-bearing land was far less than what Leopold controlled, but the rape was just as brutal. Almost all exploitable land was divided among concession companies. Forced labor, hostages, slave chains, starving porters, burned villages, paramilitary company ‘sentries,’ and the chicotte were the order of the day.”

Congolese villager being whipped with chicotte (a whip made with dried hippopotamus skin having razor sharp edges), likely for not meeting his rubber collection quota.

And what is the legacy of this exploitation and violence in Africa? For one, the arbitrary carving of Africa into nation states by the European colonial powers divided ethnic groups and helped create war and civil unrest. Further, economic impoverishment and years of dictators supported by the West (mostly to advance Cold War priorities) have left a solid foundation for political instability as well as social, political and criminal violence.

An article by Anup Shah points out:

Even as colonial administrators parted, they left behind supportive elites that, in effect, continued the siphoning of Africa’s wealth. Thus has colonialism had a major impact on the economics of the region today. Various commentators, mostly from the third world observer that colonialism in the traditional sense may have ended, but the end results are much the same.”

An interview with former Tanzania President, Julius Nyerere, is illustrative of the problems endemic to this post-colonialism region:

I was in Washington last year. At the World Bank the first question they asked me was ‘how did you fail?’ I responded that we took over a country with 85 per cent of its adult population illiterate. The British ruled us for 43 years. When they left, there were 2 trained engineers and 12 doctors. This is the country we inherited. . . .”

Anup Shah also explains how IMF/World Bank policies have basically resulted in a continuation of the colonial situation in Africa, and created an “immense burden of debt has further crippled Africa’s ability to develop.”

Bob Geldof, a member of the Africa Progress Panel, explained in a 2004 lecture:

. . .existing patterns of farming were wiped away and huge plantations of single non-native crops were developed, always with the need of European processing industry in mind.

There was a global transfer of foreign plants to facilitate this – tea, coffee, cocoa, rubber etc., The result was the erosion of the soil, forerunner of the desertification evident today. And with the erosion came steadily decreasing quantities of already scarce local food grown on marginal lands by labourers working for pitiful wages. This concentration on a few major cash crops or the extraction of an important mineral source left the countries on independence incredibly vulnerable to dramatic fluctuations in the prices of those commodities on the world market.”

“Decades of misrule,” Geldof continues, has “ left most African governments flat broke, so they [agree] to do whatever the IMF ask[s].”

Thus today, as Geldof lamented in a 2013 speech:

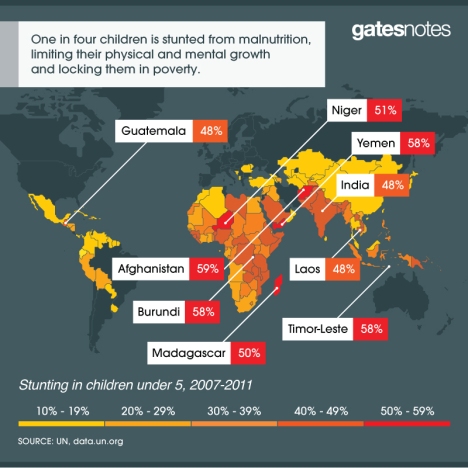

Away from the investment analyses and high growth headlines, some 40 percent of Africa’s one billion population still live on $1.25 per day or less. And, as UNICEF notes, in 2011 some 19,000 children under the age of five were still dying every day from deaths from preventable causes.”

The easy access to natural resources to maintain and fuel rebellions (combined with corporate interests) makes for a nasty combination. A lack of support for basic rights in the region, plus a lack of supporting institutions, as well as the international community’s lack of political will to do something about it and help towards building peace and stability are also contributing factors to problems in the region. As Dambiso Moyo, a former economist at Goldman Sachs and author of Dead Aid: Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is a Better Way for Africa claimed in a 2009 article in the Wall Street Journal:

Africa remains the most unstable continent in the world, beset by civil strife and war. Since 1996, 11 countries have been embroiled in civil wars. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, in the 1990s, Africa had more wars than the rest of the world combined.”

A World Bank report declares that “Seven of the 10 most unequal countries in the world are in Africa, most of them in southern Africa.”

Many countries have promised aid to Africa, but most don’t deliver, according to Jeffrey Sachs. Moreover, much of this aid is attached to requirements, as summarized in a report by the Law Library of Congress, such as a commitment “to promote democratic values” or respect human rights.

Nevertheless, as Moyo stated:

Over the past 60 years [looking back from 2009] at least $1 trillion of development-related aid has been transferred from rich countries to Africa. Yet real per-capita income today is lower than it was in the 1970s, and more than 50% of the population — over 350 million people — live on less than a dollar a day, a figure that has nearly doubled in two decades.”

Furthermore:

. . . evidence overwhelmingly demonstrates that aid to Africa has made the poor poorer, and the growth slower. The insidious aid culture has left African countries more debt-laden, more inflation-prone, more vulnerable to the vagaries of the currency markets and more unattractive to higher-quality investment. It’s increased the risk of civil conflict and unrest (the fact that over 60% of sub-Saharan Africa’s population is under the age of 24 with few economic prospects is a cause for worry). Aid is an unmitigated political, economic and humanitarian disaster.”

The article cites rampant corruption, an inefficient civil service, foreign intervention, and lack of jobs as contributing factors. The author observes:

A constant stream of “free” money is a perfect way to keep an inefficient or simply bad government in power. As aid flows in, there is nothing more for the government to do — it doesn’t need to raise taxes, and as long as it pays the army, it doesn’t have to take account of its disgruntled citizens. No matter that its citizens are disenfranchised (as with no taxation there can be no representation). All the government really needs to do is to court and cater to its foreign donors to stay in power.”

Moyo insists “It’s time for a change.” But the consequences of so many years of exploitation and a legacy of abuse and corruption make change difficult. Western countries owe it to Africa to do a better job helping root out the poisonous legacy of The Conference of Berlin.

Filed under: History, legal | Tagged: Africa, History, legal |

Leave a comment