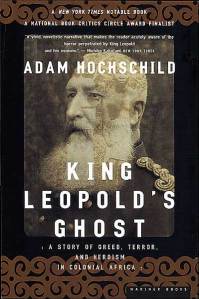

Adam Hochschild, an award-winning author of history, a journalist, and a Civil Rights worker, describes in gory detail the mass murder in the Congo that took place mostly between 1890 and 1910, under the aegis of Belgium’s King Leopold II. Leopold’s control of the Congo was marked by greed for ivory, land, and rubber. His policies were thought to have resulted in the reduction of the population of the Congo by half: an estimated five to ten million lives lost. This figure does not include the numerous people subjected “merely” to amputation of hands and/or feet, an apparently common punishment meted out to family members of recalcitrant workers. (Cutting off hands was also the practice subsequent to executions to prove one had not “wasted” ammunition on nonhuman targets. Children were often killed with the butt of guns, also to save ammunition.)

Inhabitants were used as porters – taking luggage, wine, and pâté inland for the white overseers, and bringing back ivory and rubber. They also had to harvest the ivory and rubber and process it prior to transportation. Porters were generally chained together by the neck, so that, for example, if one fell into the Congo while working on a bridge, the whole line would be dragged in as well, meaning certain death for all of them. Women were imprisoned and chained (and often raped) while the men were out gathering rubber, to ensure their return. Food allotments for workers were not generous, and punishment was meted out with the chicotte, a whip made out of dried hippopotamus hide cut into a sharp-edge strip. Beatings could be fatal. It was also not unusual for whole villages to be burned and their inhabitants executed as ‘examples” to other villages.

The author maintains that Europeans of Leopold’s time thought of Africa “as if it were just a piece of uninhabited real estate to be disposed of by its owner.” But more than that, the black inhabitants were regarded as less than human beings. Hochschild pauses in his tale of horror to ask:

What made it possible for the functionaries in the Congo to so blithely watch the chicotte in action and … deal out pain and death in other ways as well? To begin with, of course, was race. To Europeans, Africans were inferior beings: lazy, uncivilized, little better than animals. … Then, of course, the terror in the Congo was sanctioned by the [white] authorities. For a white man to rebel meant challenging the system that provided your livelihood [as well as a very good livelihood for your superiors. Leopold himself is estimated to have taken some $1.1 billion (in today’s dollars) in profits]. Finally when terror is the unquestioned order of the day, wielding it efficiently is regarded as a manly virtue, the way soldiers value calmness in battle.”

Hochschild reports that a great deal of historical detective work went into the estimation of statistics “about something [officials] considered so negligible as African lives.” On the other hand, as he ruefully observes, much data is in fact available: many officials reported meeting their “death quotas” with enthusiasm. Not all of the population loss was caused by massacre: the author delineates three other closely connected causes of death: starvation, exhaustion, and exposure; disease; and a plummeting birth rate (as a result both of the death of so many men and of the reluctance of women to bring children into their nightmarish world).

While most of the book focuses on the Congo, Hochschild’s last chapter summarizes the situation in some of the other colonial possessions. The French Congo, for instance, has a similar legacy:

In France’s equatorial African territories…the amount of rubber-bearing land was far less than what Leopold controlled, but the rape was just as brutal. Almost all exploitable land was divided among concession companies. Forced labor, hostages, slave chains, starving porters, burned villages, paramilitary company ‘sentries,’ and the chicotte were the order of the day.”

Hochschild also tells the stories of some of those who tried to bring the atrocities to the attention of the public: the tireless white crusader Edmund Dene Morel, black journalist George Washington Williams, black missionary William Sheppard, and the Irish patriot Roger Casement. Casement was hanged by the British for treason in the fight for Irish home-rule. But his self-defense at his trial spoke to the Congo as well as Ireland, and inspired – among others, Jawaharlal Nehru to go on to seek his own nation’s liberation. Casement said in a speech following his conviction for treason:

Where men must beg with bated breath for leave to subsist in their own land, to think their own thoughts, to sing their own songs, to garner the fruits of their own labours…then surely it is braver, a saner and truer thing, to be a rebel…than tamely to accept it as the natural lot of men.”

Evaluation: Hochschild is to be commended for trying to bring this true horror story back to life. There is still a need to learn from the dangers of power and greed. As he concludes:

At the time of the Congo controversy a hundred years ago, the idea of full human rights, political, social, and economic, was a profound threat to the established order of most countries on earth. It still is today.”

Rating: 5/5

Published by Houghton Mifflin, 1998

Filed under: Book Review, History | Tagged: Africa, Book Review, History |

Leave a comment