In 1924, Congress awarded WWI veterans a bonus to compensate for lost wages by serving overseas, in the form of government bonds that would collect interest over two decades, to be paid out no earlier than 1945. But in 1932, as the Great Depression deepened and frustrations mounted, jobless veterans started pressing for early payment of the bonuses.

An unemployed veteran from Portland, Oregon, Walter Waters, encouraged veterans to join a march on Washington, D.C. to lobby for passage of a bill authorizing the payouts. He convinced about 300 to “ride the rails” toward the nation’s capital. Thanks to media coverage, other veterans across the country also started jumping on freight trains and heading for Washington. On May 25, 1932, the first veterans arrived. Waters and his men arrived on the 29th. Within a few weeks another 20,000 had joined them.

Critics called these veterans “bonus seekers,” and those in their ranks the “Bonus Expeditionary Force” (BEF), a play on the “American Expeditionary Force,” as they had been called in France.

The men (many of whom brought their families) made camp in vacant lots and abandoned buildings around D.C. in areas the press called “Hoovervilles” after President Herbert Hoover, who was blamed for the economic crisis. The largest such “Hooverville,” by the Anacostia River, soon had a library, post office, a school for the children, and even a newspaper.

On June 4, the whole B.E.F. marched down the streets of Washington and spilled into the halls of Congress. On June 15, the House of Representatives passed the bonus bill by a vote of 211 to 176.

On the 17th, about 8,000 veterans gathered at the Capitol to lobby for passage of the bill in the Senate, but another 10,000 were stranded behind the Anacostia drawbridge, which police had raised to keep them out of the city. The bill was defeated. Many marchers left, but Waters and some 20,000 others declared they would not leave until they got their bonuses.

Inevitably, however, conditions in the camps deteriorated, and President Hoover, Army Chief of Staff Douglas MacArthur, FBI head J. Edgar Hoover, and Secretary of War Patrick J. Hurley feared that the Bonus Army would turn violent and trigger uprisings in Washington and elsewhere.

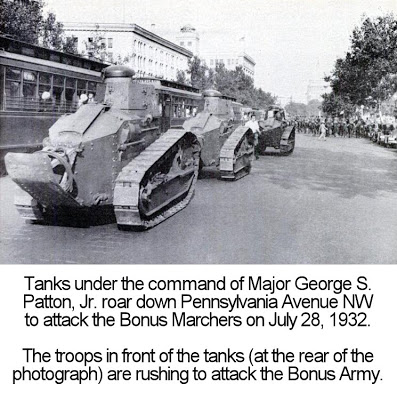

On July 28, on President Hoover’s orders, 100 policemen tried to evict the men, but the men resisted. The policemen turned to nightsticks, and the veterans fought back with bricks. It wasn’t long before the altercation involved guns. After skirmishes in the afternoon, one veteran lay dead, another mortally wounded, and three policemen had been injured.

At this point, Army Chief of Staff General MacArthur assumed personal command. Nearly 200 mounted cavalry with sabers drawn rode out of the Ellipse, followed by five tanks and about 300 helmeted infantrymen, armed with loaded rifles with fixed bayonets. Soldiers with gas masks lobbed hundreds of tear gas grenades at the crowd, setting off dozens of fires in veterans’ shelters.

By evening, the Army arrived at the Anacostia camp. General MacArthur gave the inhabitants twenty minutes to evacuate the women and children, and then led an attack on the camp with tear gas and fixed bayonets. They drove off the veterans and set fire to the camp.

Over the next few days, newspapers and newsreels in movie theaters showed graphic images of violence against the World War I veterans and their families.

For each of the next four years, veterans returned to Washington, D.C., to push for a bonus. Many of the men were sent to work on road construction projects in the Florida keys. On September 2, 1935, several hundred of them were killed in a hurricane. The government attempted to suppress the news, but the writer Ernest Hemingway was aboard one of the first rescue boats, and he wrote of his outrage, helping eliminate any residual resistance to the bonus, which was finally authorized in 1936.

Sources include:

Filed under: History, legal | Tagged: D.C., History, legal |

Leave a comment