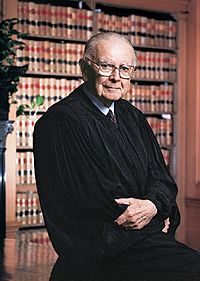

On this day in history, The U.S. Supreme Court handed down its decision on the case McCleskey v. Kemp (481 U.S. 279), which since has been widely criticized. (It was named one of the worst modern Supreme Court decisions by many sources: see, e.g., “roundups” of worse cases here and here.) Even the author of the decision, Justice Lewis Powell, stated later that he wished he could change his vote in this case.

Warren McCleskey, a Black man, was convicted of murdering a white police officer in Georgia, and McCleskey was sentenced to death.

In a writ of habeas corpus, McCleskey argued that a statistical study by law professor David Baldus, examining over 2000 murder cases in Georgia during the 1970s, showed substantial disparities in the imposition of the death penalty depending on the victim’s race, and smaller disparities associated with the defendant’s race. [Baldus, David C.; Pulaski, Charles; Woodworth, George, “Comparative Review of Death Sentences: An Empirical Study of the Georgia Experience,” Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology (Northwestern University) 74 (3): 661–753, 1983). Since that time, additional studies of other localities have confirmed that defendants who kill whites are more likely to be sentenced to death than those who kill Blacks.] Specifically, controlling for thirty-nine nonracial variables, Baldus found that in Georgia, defendants charged with killing white victims were 4.3 times more likely to be condemned to death than defendants charged with killing Black victims, and that Black defendants were 1.1 times more likely to receive the death penalty than white defendants.

However, in a 5-4 decision authored by Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr., the Court ruled against McCleskey. Justice Powell decided that the overall statistics offered insufficient proof for any particular case, writing:

The Court today holds that Warren McCleskey’s sentence was constitutionally imposed. It finds no fault in a system in which lawyers must tell their clients that race casts a large shadow on the capital sentencing process. The Court arrives at this conclusion by stating that the Baldus study cannot ‘prove that race enters into any capital sentencing decisions or that race was a factor in McCleskey’s particular case.’ . . . Since, according to Professor Baldus, we cannot say ‘to a moral certainty’ that race influenced a decision . . . we can identify only ‘a likelihood that a particular factor entered into some decisions,’ and ‘a discrepancy that appears to correlate with race.’ This ‘likelihood’ and ‘discrepancy,’ holds the Court, is insufficient to establish a constitutional violation. (emphasis in original)”

Justice Powell adduced four additional reasons he believed supported his decision:

…the desire to encourage sentencing discretion, the existence of ‘statutory safeguards’ in the Georgia scheme, the fear of encouraging widespread challenges to other sentencing decisions, and the limits of the judicial role.”

Three dissents were filed in the case, by Justices Brennan, Blackmun, and Stevens. Justice William Brennan’s passionate dissent is worth quoting at some length.

Part I of Brennan’s dissent states his belief that “the death penalty is in all [emphasis added] circumstances cruel and unusual punishment forbidden by the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments.”

Even aside from this consideration, Brennan did not agree that the prospects of equal treatment for Black defendants in Georgia were fair and balanced, as it were. He emphasized that regardless of whether McCleskey could prove racial bias, the very likelihood of it should be sufficient for an Eighth Amendment claim:

Since Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972), the Court has been concerned with the risk of the imposition of an arbitrary sentence, rather than the proven fact of one. Furman held that the death penalty may not be imposed under sentencing procedures that create a substantial risk that the punishment will be inflicted in an arbitrary and capricious manner.”

Brennan adds his own statistical analysis of the findings, declaring:

. . . The rate of capital sentencing in a white-victim case is . . . 120% greater than the rate in a black-victim case. Put another way, over half — 55% — of defendants in white-victim crimes in Georgia would not have been sentenced to die if their victims had been black. Of the more than 200 variables potentially relevant to a sentencing decision, race of the victim is a powerful explanation for variation in death sentence rates — as powerful as nonracial aggravating factors such as a prior murder conviction or acting as the principal planner of the homicide.”

But, he goes on, there is more.

Data unadjusted for the mitigating or aggravating effect of other factors show an even more pronounced disparity by race. The capital sentencing rate for all white-victim cases was almost 11 times greater than the rate for black-victim cases. Furthermore, blacks who kill whites are sentenced to death at nearly 22 times the rate of blacks who kill blacks, and more than 7 times the rate of whites who kill blacks. In addition, prosecutors seek the death penalty for 70% of black defendants with white victims, but for only 15% of black defendants with black victims, and only 19% of white defendants with black victims. (emphasis in original)”

He concludes on this point:

The statistical evidence in this case thus relentlessly documents the risk that McCleskey’s sentence was influenced by racial considerations.”

He adds that in the case of Georgia, “the conclusion suggested by those numbers is consonant with our understanding of history and human experience.”

He then proceeds to answer Justice Powell’s other objections to finding for McCleskey, which you can read here.

Justices Harry Blackmun and John Paul Stevens also dissented, deviating from Brennan in that they were not willing to rule out any death penalty cases. For his part, Brennan differed from Blackmun and Stevens in their belief that guidelines about what constituted “extremely aggravated cases” would minimize the risk of discriminatory enforcement of the death penalty and that “narrowing the class of death-eligible defendants is not too high a price to pay for a death penalty system that does not discriminate on the basis of race.”

Reverberations from the majority in the McCleskey decision reached far beyond the case of Warren McCleskey, creating a burden of proof almost impossible to meet. Blume, et al. argue that there are compelling reasons to read McCleskey narrowly. [John H. Blume, Theodore Eisenberg, and Sheri Lynn Johnson, “Post-McCleskey Racial Discrimination Claims in Capital Cases,” 83 Cornell L. Rev. 1771 (1998, available online here.) Nevertheless, they observe, “most lower courts reject post-McCleskey capital-sentencing racial discrimination claims without any individualized analysis.” (Id., at 1780—1781.) Indeed, the entire process of the criminal justice system has continued to discriminate against Blacks, from arrest, to treatment by police, to juror evaluation, to rates of imprisonment, to assignment of the death penalty.

According to Adam Liptak in The New York Times:

‘McCleskey is the Dred Scott decision of our time,’ Anthony G. Amsterdam, a law professor at New York University, said in speech last year at Columbia. ‘It is a decision for which our children’s children will reproach our generation and abhor the legal legacy we leave them,’ said Professor Amsterdam, who worked on the McCleskey case and many other capital punishment landmarks.”

And as Blume et al. conclude (Id. at 1809-1810):

Fear of labeling state officials racist, the need for prosecutorial discretion, and general reluctance to address racial claims all may fuel the doctrinal missteps in post-McCleskey county-level cases. An understanding of courts’ reluctance is not, however, a reason to condone such action. Judges, especially federal judges, enjoy constitutionally protected independence precisely because they must make unpopular and difficult decisions. In the proud modern history of the judiciary, judges’ finest hours have come by challenging discrimination rather than sheltering it. It would be ironic if they now were to afford racial discrimination its greatest shelter, through heightened burdens of proof, in cases involving life and death.”

Leave a comment