Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. was born in Boston in 1841. He graduated from Harvard, served in the Civil War (he was wounded three times), and then returned to Harvard for law school.

Daguerreotype showing Holmes in his uniform, 1861

After graduating, he entered private practice. Then he returned to Harvard once again, this time to teach constitutional law. He also published a treatise, The Common Law. He served twenty years on the Massachusetts Supreme Court. In 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt nominated Holmes to the Supreme Court, a position for which he was confirmed without objection two days later.

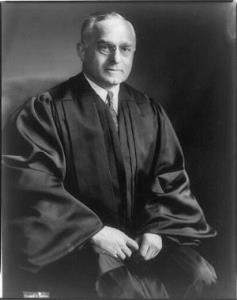

In the year of his appointment to the United States Supreme Court

Holmes served as Associate Justice from 1902 to 1932, and in 25 of his 29 years on the Court, never missed a session. Today, he is one of the most widely cited United States Supreme Court justices in history, particularly for his “clear and present danger” opinion representing a unanimous Court in the 1919 case of Schenck v. United States. He retired from the Court at the age of 90 years on this day in history.

The Great Dissent: How Oliver Wendell Holmes Changed His Mind–and Changed the History of Free Speech in America by Thomas Healy is a very thought-provoking account of how Justice Holmes altered his position on freedom of speech to pave the way for the more liberal interpretation of the First Amendment we now regard as canonical. In the short period between his 1919 decisions in Schenck v. United States, Frohwerk v. United States, and Debs v. United States, and his decision in Abrams v. United States, Holmes changed his mind and changed the law.

It’s an interesting and important story for several reasons. One is the view it provides of the rather astounding effect that one Supreme Court Justice can have on the law of the entire country. Holmes’s famous dissents arguing for an expanded view of First Amendment freedoms were not as well-written as those of Brandeis, to name but one other advocate who wrote more clearly, but it was Holmes, with his far-reaching influence and “force of personality” that affected the public consciousness, and, as Healy writes, “gave the movement its legitimacy and inspiration.”

A second fascinating aspect of this story is its recounting of just how and why Holmes was influenced by his coterie of friends. This group was made up of young intellectuals who came under government suspicion because of their backgrounds and liberal tendencies rather than because of any danger – either from intent or from effect – of their speech.

Finally, there are the compelling philosophical issues about the First Amendment itself over which Holmes struggled: where should the line be drawn for freedom of speech? If the country is at war, must “all rights of the individual… become subordinated to the national rights in the struggle for national life” as one critic argued? Should war make a difference? If so, why? What if the war itself is unjust? And what about the difference between the intent of speech and its effect? Is it fair to ignore one or the other?

So what exactly happened between Schenck, decided March 3, 1919, and Abrams, decided November 10, 1919? This entertaining book by Healy answers that question.

Holmes was not initially in favor of toleration of other opinions. He didn’t believe in “natural rights.” (He had just recently written, “…there can be no legal right as against the authority that makes the law on which the right depends.” Kawananokoa v. Polyblank.) Also in 1907, his opinion for Patterson v. Colorado enshrined into law a “Blackstonian” view of free speech, which insisted that the purpose of the First Amendment “was to prevent all such ‘previous restraints’ upon publications as had been practiced by other governments, but not to prevent the subsequent punishment of such as may be deemed contrary to the public welfare.” (After publication, however, as the author commented, “all bets were off.”)

But Holmes had a number of very close friends – young, mostly Jewish intellectuals, a couple of whom he considered to be like his sons. Included among them were Harold Laski, Felix Frankfurter, Zechariah Chafee, and Louis Brandeis. These men had much more liberal ideas than Holmes on a wide array of subjects, including free speech, and they plied him with books to show him how their thinking had evolved. He happily read them, and engaged in debate with his friends, but resisted change.

Justice Felix Frankfurter

However, after World War I, the mood in the country took a turn for the worse. A “Red Scare” following the Russian Revolution swept America. Congress passed the Espionage Act in June 1917 and the Sedition Act in the spring of 1918. U.S. officials, led by the Attorney General and a young J. Edgar Hoover, who in 1919 was put in charge of the “Radical Division” at the F.B.I., eagerly stoked the flames, embarking on witch hunts for anyone deemed “suspicious”. The Washington Post, reflecting the mood of the nation, wrote, “Too long the government pursued the policy of waiting until some overt act was committed before talking steps against the anarchists…” And as the author pointed out:

Many of these [suspect] people, it was said, were teaching at universities, where they could corrupt the minds of the young. Many others were immigrants, particularly of Jewish ancestry. And for those unfortunate individuals who were both university professors and Jewish immigrants, well, the presumption of guilt was nearly automatic.”

Holmes’ friends Laski, Frankfurter, and Chafee were professors at Harvard, and Brandeis was on the Supreme Court. Brandeis enjoyed relative immunity compared to the others, who soon found their careers in jeopardy. This was probably the best thing that happened to free speech. As Healy observes after Laski came under fire:

For now what had been merely an abstract question for Holmes over the past year was, suddenly, concrete and personal. The face of free speech was no longer Eugene Debs, the dangerous socialist agitator. It was his good friend Harold Laski, and Holmes’s views shifted accordingly – and dramatically.”

It wasn’t just a case of Holmes liking these men and therefore feeling disposed to advocate on their behalf. He knew they posed no threat to the country, and that their ideas were not threatening but stimulating, and grounded in centuries of philosophical and legal debate. He argued in Abrams not only that one needn’t worry because “bad” opinions would suffer accordingly in a free marketplace of ideas. He went further, disavowing the idea that free speech is inapplicable during times of war, reemphasizing the “clear and present danger” criterion he had first articulated in Schenck. He had come to see the raft of cases brought under the Sedition and Espionage Acts as part of the government’s effort to impose uniformity of belief, and he opposed that effort. In yet another dissent, for the 1929 case United States v. Schwimmer, he wrote:

…if there is any principle of the Constitution that more imperatively calls for attachment than any other it is the principle of free thought – not free thought for those who agree with us but freedom for the thought that we hate.”

He still felt that “persecution for the expression of opinions seems…perfectly logical.” But now he added – as John Stuart Mill had maintained in On Liberty, a book recommended to him by Laski – that opening up beliefs to refutation will only strengthen them if in fact they cannot be proven to be unfounded.

Evaluation: This is a highly interesting story and well-told, except, that is, for the prologue and first chapter. I thought the book would have been enhanced by omitting those two portions. Also, the author somewhat bizarrely and irrelevantly, as far as I could tell, decided to add information about Holmes’ love life. I saw no possible reason for it to be included.

Rating: 4/5

Published by Metropolitan Books, 2013

Filed under: Book Review, SCOTUS | Tagged: Book Review, SCOTUS |

Leave a comment