Brexit is a portmanteau of “British” and “exit”. In popular usage, it was derived by analogy from Grexit, referring to a hypothetical withdrawal of Greece from the eurozone (and possibly also the European Union, or EU).

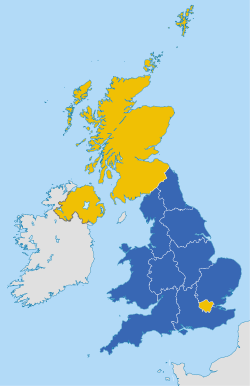

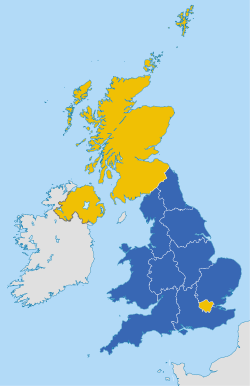

In a referendum on June 23, 2016, 51.9% of the participating UK electorate voted to leave the EU; the turnout was 72.2%. England voted for Brexit, by 53.4% to 46.6%. Wales also voted for Brexit, with Leave getting 52.5% of the vote and Remain 47.5%. Scotland and Northern Ireland both backed staying in the EU. Scotland backed Remain by 62% to 38%, while 55.8% in Northern Ireland voted Remain and 44.2% Leave.

Results by region:

Blue: Leave

Gold: Remain

As Sam Knight in “The New Yorker Magazine” observed:

….the E.U., a vast supranational project …. had become a metaphor for a remote and unfair system for organizing people’s lives. But the decision presented a great democratic problem. Staying in the E.U. could mean only one thing, but there were any number of ways to leave. No country has ever left the E.U., and the states on its borders have a spectrum of relationships with the bloc.”

Britain, Europe’s financial center, joined the European Economic Community, as it was then known, in 1973. Since then, Britain imported around nineteen thousand European laws and regulations. Although populists called for the U.K. to “take back control,” the racial card of immigration played a large role.

In addition, a great deal of misinformation and false claims debunked here was disseminated to the electorate prior to the election, including:

1. ‘The money saved from leaving the EU will result in the NHS getting £350m a week’

2. ‘A free-trade deal with the EU will be ‘the easiest thing in human history’

3. ‘Two thirds of British jobs in manufacturing are dependent on demand from Europe’

4. ‘Turkey is going to join the EU and millions of people will flock to the UK’

5. ‘Brexit will lead to Scotland renewing calls for independence’

6. ‘Brexit does not mean the UK will leave the single market ‘

Moreover, a series of allegations regarding Russian influence over the vote were investigated, and some called for a new referendum. The London Observer reported that it reviewed documents suggesting there were multiple meetings between the leaders of the Leave.EU movement and high-ranking Russian officials between November 2015 and 2017, two of which were said to have been held the week that Leave.EU launched its official campaign. In addition, there are suggestions Russian money used as bribes to the Leave.EU leadership was involved.

Gary Barker – Credit: Archant, via The UK New European

An article from Britain by Louise Chunn on the psychology of those who accepted the lies about Brexit notes:

. . . many of those who were convinced to vote to leave EU did so because they want to believe that £350 million would be taken from our payments to that blood-sucking ‘European’ bureaucracy, and returned to feed our own ‘British’ NHS.They were also told that their vote would enable them to ‘Take Back Control’ —- apparently a slogan introduced to the campaign by hypnotist and self-help author Paul McKenna, who uses such techniques when hypnotising clients and in his best-selling books such I Can Make You Thin or I Can Make You Rich. People lapped up the sales pitches.”

David Cameron, the Conservative party Prime Minister who had called the referendum, resigned immediately. Theresa May, also a member of the Conservative Party, became the new Prime Minister twenty days after the British people voted to leave the European Union. Theresa May was against Brexit during the referendum campaign but afterward claimed she supported it because, she says, it was what the British people wanted (or in any event, thought they wanted).

David Cameron and Theresa May

In the U.K. there was chaos. As “The New Yorker” Magazine reported:

As Prime Minister, May immediately established two new government departments: Dexeu, to manage the Brexit process; and the Department of International Trade, to explore economic opportunities outside the E.U. Dexeu was given offices at 9 Downing Street, the former premises of the court of the Privy Council. In their first weeks, civil servants worked in the docks and on the benches of the old courtroom as they grappled with the scale of Brexit. ‘People were saying, ‘How does the U.K. fishing industry work? How does the U.K. automotive industry work?’ the senior official told me. ‘You were getting papers saying, ‘There are lots of fish in English waters.’ Literally, they were at the most basic level.’”

Joseph M. Hassett, author of a book about Yeats and his influence (Yeats Now: Echoing Into Life, 2020), noted that the morning after the UK electorate voted for “Brexit,” the line “The centre cannot hold” from Yeats’ poem “The Second Coming” “was tweeted or retweeted 499 times….”

Withdrawal from the European Union is governed by Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union. Under the Article 50 invocation procedure, a member notifies the European Council, whereupon the EU is required to negotiate and conclude an agreement with [the leaving] State, setting out the arrangements for its withdrawal, taking account of the framework for its future relationship with the [European] Union. The negotiation period is limited to two years unless extended, after which the treaties cease to apply.

The UK Supreme Court ruled in January 2017 that the government needed parliamentary approval to trigger Article 50. Subsequently, the House of Commons overwhelmingly voted, on February 1, 2017, for a government bill authorizing the prime minister to invoke Article 50, and the bill passed into law as the European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Act 2017. Theresa May then signed a letter invoking Article 50 on 28 March 2017, which was delivered on March 29 to the European Council President. The UK stopped being a member of the European Union (EU) on January 31, 2020.

As Euronews reported:

No sooner had negotiations begun on the UK’s post-Brexit relationship with the EU, than the coronavirus pandemic effectively put a halt to proceedings. . . . Video connections are not seen by critics as a satisfactory substitute for face-to-face meetings, given the detail involved and the dozens of negotiators on each side.

Recent months have seen energies on both sides distracted by the pandemic, but very soon decisions will need to be taken on post-Brexit ties.”

You can keep up with Brexit-related news as it unfolds on the UK Telegraph site, here as well as the online BBC. Details of Brexit are still being hammered out for every aspect of life, such as revealed in this May 29, 2020 article:

The European Union will reject British demands for stronger legal protection for UK regional products such as Stilton cheese and Scottish whisky after the end of the Brexit transition period in trade negotiations next week.

The UK agreed to keep EU protections for delicacies like champagne and Parma ham in place and in perpetuity in negotiations over the Withdrawal Agreement – but failed to secure the same guarantees for British products in the EU.

While EU product protection is now enshrined in an international legally binding treaty, British products will only be protected under EU law if they remain on the EU’s register of Geographical Indications (GIs).”

You can learn more details about Brexit in a very informative FAQ from the BBC, here. There is also the latest news on Brexit from the New York Times as of May, 2021, here. This article from July 15, 2022 shows more trouble is ahead for Brexit, centering on the Ireland question.

Filed under: legal | Tagged: Britain, History, legal | Leave a comment »